Knowing is not doing. I know meditation helps me. Yet I’m not meditating every day. I know playing blitz games without focus isn’t fun or good for my chess. Yet you’ll find some of those games in my Lichess & Chess.com profiles.

In the same way, just having some knowledge about chess (doubled pawns are bad, don’t get into time trouble, play with all your pieces…) won’t automatically lead to good decisions during a game. In order to translate knowledge into results you need skills. And skills are gained when you test your knowledge in practice.

That results in a simple equation:

Knowledge + Skills = Good Moves

In this article, I will explain how you can both get knowledge and skills in chess. This way you won’t only have theoretical wisdom, but also practical results!

Theoretician vs Street Chess

It is very likely that you are part of one of two groups:

Group A: The ‘truth’ searchers: Love to learn, full of chess wisdom but lack practical abilities

Group B: Competitive Type: In it for the practical aspects, find theoretical study rather boring

None of the groups is better or worse. When it comes to optimal improvement, one needs to be a mix of both groups.

Why?

Because Knowledge without skills is only potential power. Sitting at home you often know what you should play. But as soon as you are at the board, you make bad decisions because you lack the skills.

And Skills without knowledge is pure, mostly unsound, ‘street chess’. You will often be able to trick your opponents, but you can’t cover up your lack of the fundamentals forever. At some point, people will stop falling for your tricks and you have a hard time progressing.

So, the optimal way of getting better at chess is:

- Acquiring Knowledge (what I call ‘learning’)

- Getting the skills (what I call ‘improving’)

How can you do that?

Let’s take Anastasia’s Checkmate as an example.

Learning Anastasia’s Checkmate

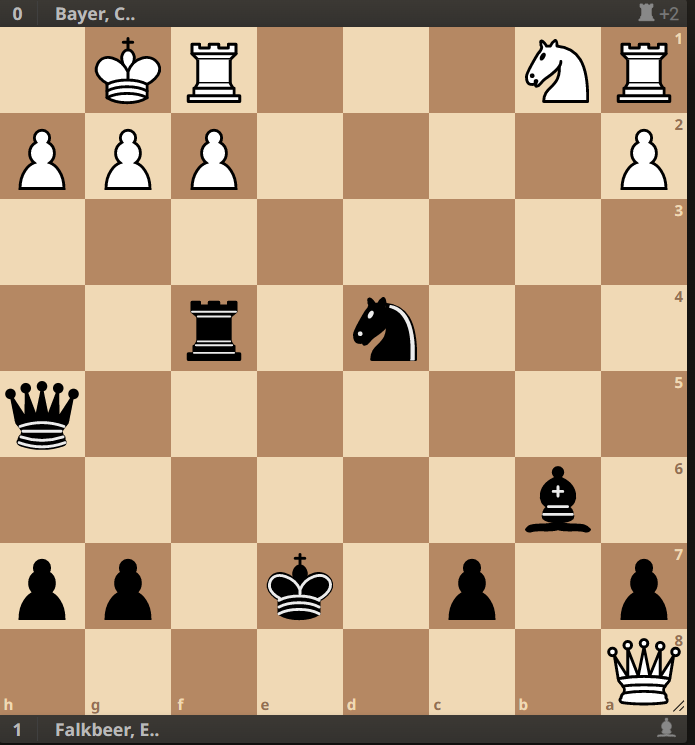

If you have never seen the Anastasia’s Checkmate before, I guess you will have a hard time solving the following position:

So you need to learn this new motif before you will be able to implement it. Here is how the Anastasia’s Checkmate works:

- Knight on e2 covers up the g1&g3 escape Squares for a King on h1 or h2.

- Pawn on g2 blocks this important square for the King.

- Rook or Queen delivers a deadly check along the h-file.

This obviously also works on the 3 other corners of the board with a Knight on d2 (Black) or e7/d7 (White). Now look at the position above again: can you construct this checkmate?

1…Ne2+ 2.Kh1 Qxh2!! (opening up the h-file) 3.Kxh2 Rh4# is the solution.

Once you know what you are looking for, things become much easier. It is one thing to find a checkmate when you KNOW that there is one. During the game, you don’t have the privilege of knowing what to look for. So how do you go now from Learning the checkmate to delivering such a combination in a real game?

By practicing it over and over again. And here is how.

Improving Anastasia’s Checkmate

Going from theory to practice needs some time. That’s why I use three in-between steps to make the process more simple:

Step 1: Learn a new motif

Step 2: Use the motif with hints

Step 3: Use the motif without hints, still knowing there is a tactic

Step 4: Find a motif in a position that could also have no solution

Step 5: Deliver a deadly checkmate in your own game

You might realize: Learning is only 1 step while improving takes up the remaining 4 steps.

That explains the 10’000 hours rule, which says that you get expert at something only if you put in at least 10’000 hours of practice.

Learning the basic motifs & ideas in chess doesn’t take up too much time. What really differentiates players is if they are ready to put in the time to improve their skills.

Learning vs Improving

This learning + improving cycle does not only apply to a new tactical motif. The same goes for openings, endgames & strategy. You might ‘know’ how to hold a Rook Endgame a pawn down thanks to the Philidor defense.

But then in a game with seconds on your clock you somehow still mess things up. That’s again a sign of good theoretical knowledge but not enough skills.

Why is it that most players seem to have a lot of knowledge but only a few really have the skills?

The answer is quite simple:

- Acquiring knowledge is easy & fun

- Improving the skills is hard & repetitive

Learning

Learning is mostly done in a classroom-type setting. Someone is teaching you something new. You can do that either with a Coach, by watching videos, or by reading a book.

The additional knowledge you get immediately makes you feel smarter.

When others explain these things, everything seems simple. You can even learn things when you aren’t fully paying attention.

Improving

Improving on the other hand is mostly done by yourself. This is either you playing a game and analyzing your decision-making afterwards, or you solving difficult positions. Nobody is there to help you. You are going to make mistakes and sometimes you might feel stupid afterward.

When you learned the basic tactical motifs they seemed so simple, but solving positions where you don’t know which motif to apply is actually hard! You can’t really do this lying on your couch or trash-talking your friends. Improving needs full attention.

But let me tell you: if you do this over a period of time, your results will get a lot better.

Learning + Improving In Practice

Now that you know the difference between Learning & improving you might need some practical tips to ensure you do enough of both.

Tip #1: Be Aware of Your Tendencies

Awareness is the first step to improvement. What comes more naturally to you, learning or improving? If you have a hard time finding out, write down what you spend your time on in chess training for the next week.

Divide all activities into two categories. For example:

Monday, 5-6 PM, watching my favorite streamer → Learning

Tuesday, 4-5 PM playing + analyzing games → improving

At the end of the week, you should have a pretty good feeling if you rather learn or improve.

Tip #2: Learn Something New Every Week

The game of chess is nearly limitless. There is so much to learn! Be curious and try to learn something new every single week. You can do that by reading articles just like the one you are reading, getting a good book, or joining a group class.

Whatever sparks your curiosity is fine. Just make sure you still have some time left to improve on what you learned.

That brings us to

Tip #3: Always use What You Learned

Whenever you learn something new, make sure to apply it immediately in training, or best case, in your games. This improvement process will most likely take much longer than the learning process, but that is fine.

Remember that to achieve mastery you need to put 10’000 hours into something. Of those 10’000 hours, most likely 9’000+ will be spent improving.

So when you learn a new motif, make sure to immediately solve some puzzles with that motif. If you read about tricks to get rid of your time trouble habit, play the next games with these tricks in mind.

If you follow the three tips above, you will make sure that you keep learning & improving every single week. And soon enough your friends will ask: how did you get so strong?

By combining learning & improving.