Reaching the Grandmaster (GM) title was a long-standing dream for me. After scoring my first GM-Norm in 2014, I had to wait 3 more years until April 2017 to achieve the Grandmaster title.

While the progress until the International Master (IM) title was pretty smooth, the road to the Grandmaster title was really hard.

Be it my opening repertoire, how intensely I trained, and also the people around me. I had to change everything to make the step from IM to GM.

In this article, I want to guide you through my process from IM to GM. By learning from my mistakes and lessons, I hope you will find it easier to take your chess to the next level.

If you don’t know yet how exactly one reaches these titles and want some background on them, then this article is for you.

How I Got The IM Title

Before we get to the step from IM to GM, I want to tell you how I got to the IM title in the first place. This will paint the full picture, so you can really understand the big switches I had to make.

In 2008, aged 12, I played my first European Youth Championship (U12). I then got my first FIDE rating in January 2009: 1918. I entered the Swiss Youth Team and was able to train with IM Oliver Kurmann and GM Artur Jussupow.

Obviously, that is a great way to progress. But even though I also went to a sports High-School starting in the Summer of 2010, I was not really investing a lot of time in chess. I had about 2-3 1.5h Training sessions per week and played some tournaments.

Overall I would say I averaged 2 hours of Chess per day during this period. This is a serious amount for a hobby, but nothing compared to what I did later on.

Every day I had some exposure to chess. My main exposure was checking online games (without engines!). Reading Chess books or straining myself with some calculation training was not really on my to-do list.

I did not feel like I had to put in too much effort, because I continuously improved my chess. Neither did I think of a professional Chess career back then.

I did not really make an effort to improve my physical abilities, nor did I work with a sport psychologist. I simply played chess, improved upon my games, and spent some free time analyzing things that interested me.

After 5 years of averaging about +100 rating/year, I got my IM title in October 2014.

Sudden Change Of Approach

My mindset and approach to chess rapidly changed with the World Youth Championship in Durban (South Africa) in late 2014. I had never thought of having a chance to compete for Youth titles internationally.

But there I was, sitting on Board 1 in the last round of a U18 World Championship.

A draw basically assured me the bronze medal, but I wanted more. With a win, I had the chance to tie for first place and maybe be crowned World Champion.

A medal would have meant the first World Youth Championship medal for Switzerland since 1971!

Even though I lost a miserable game (after rejecting a draw offer!), I suddenly started to believe in my chances, even internationally. The GM title did not seem that far away after all.

And with the notion of “we Swiss players anyway can’t seriously compete internationally” gone, I even started to dream of more than “only” the GM title.

But I knew that my approach needed to change if I really wanted to compete internationally.

What Do I Lack For The GM Title?

As I only had half a year of school left, I started thinking about a professional Chess career.

As my parents were (and still are) not really fond of it, I just told them I wanted to take one sabbatical year for Chess.

This year turned out to be a second, and now I am a professional Chess player for 6 years already.

So I had two reasons to step up my approach and dedication:

- To reach my newly formed goals

- To convince my parents that a sabbatical year is not just chilling time

Starting to think a bit more professionally, I soon realized it will take more than 1-2 small adjustments.

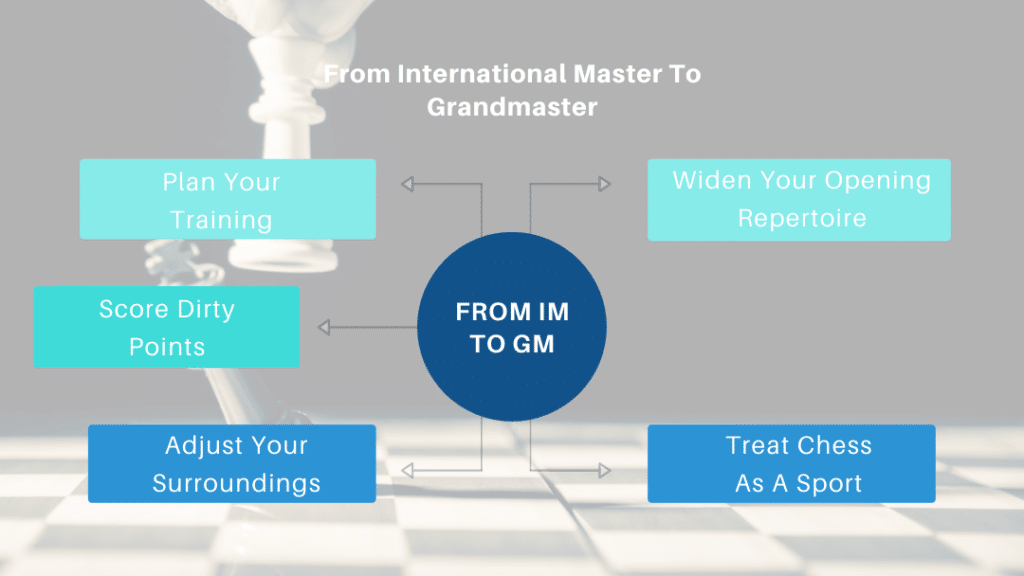

I came up with a list of things I thought were important to take my Chess to the next level and beyond that.

- Opening Repertoire:

My repertoire was extremely small back then. With white 1.e4 and with black Nimzo against 1.d4 and the French against 1.e4. I needed to widen my repertoire and also analyze openings more deeply. - Planning Training:

Back then I simply did what I felt like doing. Having a full year without school, I needed to organize my training. And most importantly, I needed to be ready to strain myself in training. - Making dirty points:

I was famous for outplaying even much stronger opponents and then still losing these games. I had to find a way to convert more positions. And also to win some games where I was in big trouble or simply played worse. - Adjust my surroundings:

When I was small, I always made fun of Chess professionals. I said it was literally impossible to live from playing Chess in Switzerland. Now that I had changed my mind, I needed to make sure my surroundings were not influencing me negatively. This meant changing who I hang out with (from the “cool kids” to the “nerdy Chess pros”) and later also who I worked with. - Treat Chess as a Sport:

This meant seriously thinking about what can improve my performance. In the process, I improved my mental & physical condition with several tools and the aid of great people.

1. Opening Repertoire

The first thing I wanted to change was my white repertoire. It came in handy that GM Boris Avrukh just published an expanded and updated version of his Catalan Repertoire Book (1A; 1B) back in April 2015.

So I did something I had never done before: working with a book on my repertoire. It may be hard to imagine, but only 6 years ago there were basically no online courses on opening.

Going through this whole book and typing every single line into Chessbase was a huge effort. For the first 1-2 months I solely worked on understanding this new opening, improving or prolonging the lines he suggested.

This might seem like a crazy amount of time I invested. But I have used this opening ever since for now around 6 years. So it definitely was a good long-term decision to do so.

Even now I would still do it similarly.

Actively typing all move into Chessbase and thinking if a line is important or not is crucial when it comes to understanding and remembering an opening.

You might be much faster by simply watching some videos or checking an opening file you bought. But you will need to repeat the same things over and over again because you are only watching passively.

Learn how to study video courses and still remember the opening in this amazing article.

Additionally, you won’t understand the position in the same way. If you decide to do it with an online course, then try to be active while watching it. Ask questions and try to understand the reasoning behind the moves!

Next up was the Queens-Gambit-Accepted against 1.d4. I analyzed the opening with my new Coach (November 2015-Summer 2017) GM Iossif Dorfman. As these were two totally fresh openings, we decided to stay with the French against 1.e4 for now.

We simply went much deeper and searched for alternatives in all the critical lines. Instead of playing 3…Nf6 against the Tarrasch (3.Nd2) I started playing 3…c5.

Diversifying an opening repertoire does not need to be done by adding totally different openings. It is already a great step if you find different alternatives in the lines you are used to playing.

While it does not have the same surprise factor for opponents, it is a much less time costing way to avoid playing the exact same thing all the time.

If you decide to play a new opening, you need to be patient. Long-term it will most likely pay off. But in the short term, you might lose some games because you are not too familiar with the new structures and ideas.

Playing a new opening is a learning process!

So don’t quit after losing some games. Keep at it and give the new opening a real chance.

As you learn the new opening better, there is a great side effect: your old opening will now come as a surprise to your opponents!

They have to prepare more and don’t know what to expect. In the long run, that should make both opening choices better.

2. Planning The Chess Training

I am now very fond of training plans. But some years back I did not do them at all. Over time I started to understand the importance of and how to do it right.

There are several aspects to planning Chess training. I have divided them into three different categories.

Here we go:

Periodization

One thing I understood pretty quickly is the importance of different periods. It is nearly impossible to work on long-term things as a new opening repertoire if you have a tournament around the corner.

That is why I always plan a period where I play few or nothing at all.

From October 2015 – February 2016, I played only 16 games. That is an average of 3 games per month as a new professional Chess player.

I then used the new openings and the better training from March-August. This playing period started with a rating of 2408 In January 2016 and peaked with the Swiss Champion title and a rating of 2477 in August 2016.

So let me tell you again: working on the basics, such as a new opening repertoire, calculation, and psychological weaknesses is nearly impossible if you play a tournament every 3 weeks.

What sounds strange for (Amateur) Chess players, is totally normal in other Sports.

There are periods when a sportsperson works on the basics (off-season) and then there is the season, where one competes a lot and tries to be in great shape.

Be it Football, American Football, Swimming, or basically any other sport: one does the basics in the off-season and then uses them during the season.

As a matter of fact, some Top Chess Players do the same thing. Before the World Championship Match, the two contestants are usually working deeply without playing (a lot).

This is the deep work they need to do to be ready for such a testing match. The same idea can be applied to Amateurs or new professionals as well.

I have also written about periodization in my article on tournament preparation.

Writing A Training Plan

Writing a training plan is key to the success of a Chess player. There are so many things one could do to improve in Chess. If you try to decide this every time you sit down to train, you will be exhausted before you even start.

And chances are big that you will go for the most convenient, not the most effective training.

All of these struggles can be solved with a training plan. I started and stuck with a weekly plan, usually written on Fridays for the coming week.

If you want to know more about training plans, then please read my in-depth article on doing one for yourself.

Going To The Limits

Training only works efficiently if we go to our limits. As I explained before, I wasn’t ready to do so. My main goal was to increase the intensity of my training in small steps.

It is literally impossible to go from “just analyzing a bit with the Computer” to “full calculation for 3 hours straight” in one day. I had to do it in small steps.

Even the time I focused on my new Catalan opening, I started the day with 30 Minutes of focused tactics. 30 Minutes might not sound like a lot. But over time, I built muscle and could improve upon that.

After doing that for 2 months straight, I was now ready to pick up Calculation by GM Jacob Aagaard out of his great Grandmaster Preparation series.

It still was a really tough book for me to work through. But I believe the benefits of that hard training were huge.

These benefits are only big if you manage to do some highly focused and energetic training.

I am sure it would have been very discouraging to work on it first thing in August 2015 with a monkey mind. As I never really did really focused training before, I needed to slowly work towards such a challenge.

The worst thing you can do when working towards a big goal is discouraging yourself with books and puzzles that are way too hard. I sometimes hear of 2100 FIDE players that pick up that same book and tell me “I suck at calculation”.

Well, the book is not really aimed at 2100 FIDE, so it is absolutely no surprise if you get every position wrong. So go to your limits, but stay realistic.

Find the balance between having to focus 110% on training and also finding solvable books/puzzles.

Just sitting there and clicking on the computer with the help of an engine is horrible. But sitting at the board and calculating for 60 minutes without even getting close to the solution is also horrible!

A good rule of thumb is the following: you should be able to solve 60-70% of the puzzles right in 15 Minutes. If you get 90% after 5 Minutes, the book is too easy.

If you fail at more than 40%, you should maybe put the book aside for a moment and find an easier one for the moment. You can find different books on my resources page.

3. Making Dirty Points (image vs Fier, image when I won dirty)

One thing that always impresses me about big Champions is that they manage to win even on bad days. Nothing seems to go their way, their opponent is outplaying them, but somehow they manage to still win the game.

I was (and still am sometimes) on the wrong side of things a lot of times. So many times did I get winning positions against Grandmasters, but then they somehow tricked me and won. It is such a horrible feeling.

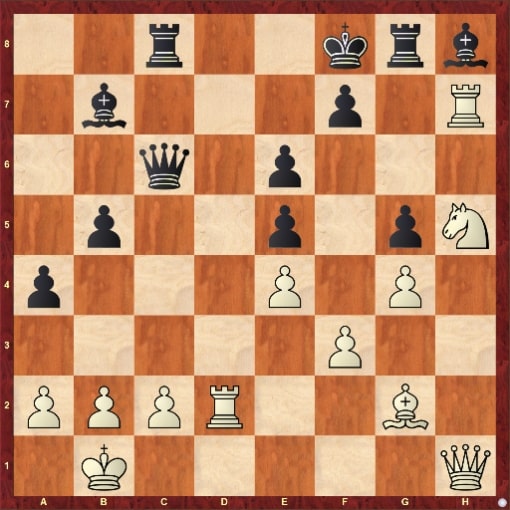

This all started as early as 2011 when I was rated 2180 and played against Grandmaster Fier with a rating of 2580. After a big fight in the Sicilian, I got a position one should never lose.

It seems like white is in full control. Blacks rook and Bishop on g8 and h8 are totally out of play. With Qd1! I could have basically finished the game. I am threatening Rd8+, Rd7, and Rd6xe6 and Black cannot stop all of them.

Even without this move, my position is far superior. But only in a few moves, Fier managed to activate his g8-Rook via d8, open my king and go into a slightly better endgame.

The theme became very clear to me over time.

Instead of always saying my opponents were “so lucky, but I am playing much better” I needed to understand why I kept being on the wrong side of things.

I have already written on how to convert a winning position. So here I would like to focus on the art of scoring on bad days.

Scoring on bad days requires:

- Mental stability

- Energy

- Tactical imagination

Mental Stability

As I always wanted to win, I usually lost interest in the game very quickly whenever I got into a worse position. I did not see the “sense” in fighting on.

It seemed like in the greatest case I would get half a point, which was also not what I was really excited about. Usually, I was less focused in bad positions and gave the game away too easily.

What helped me was really counting all the points I threw away because of my lackluster play in worse positions. It was around 1 point per tournament (9 games). This means 10 rating points for each tournament.

If you start to count this for a whole year, it is a lot. It seemed I could nearly make it to the GM title by simply defending better.

I want to share one mental trick that helped me in worse positions:

As I was prone to lose focus, I needed to set small challenges during the game to keep myself interested.

In lost positions, this could simply be: find 5 more moves that don’t lose material immediately. In bad positions, I would say myself to find 5 moves without making the position even worse.

Now instead of just going for a cheap trick and losing very fast, I started to put up some resistance. And more often than not, my resistance led to mistakes from the opponents.

So until this day, I try to set myself small achievable challenges in bad positions. This leads to more fun during the game, and also much better results out of unfavorable positions.

Energy

Obviously, energy is needed in any kind of position. But by having an inferior position, the best chance usually is to keep that inferior position as long as possible. Just not to lose immediately.

So the end is not very near for you. Well, it might be, but then you usually lose… That is why having lots of energy is required to defend better.

With mental stability AND a lot of energy, you have great chances to keep the position how it is and not make it even worse.

It is important to note the following: an attack or trick usually only works out of a sound/better position.

If your position is worse, you usually have less active pieces. So whenever you try to “get the game over fast” you risk giving your opponent an easy way to finish the game off.

Talking of your opponent: it is most unpleasant in a good position if the defending side simply keeps playing on without getting nervous.

The longer you manage to do so, the more chances you will get!

Tactical Imagination

This is something that some people have by nature. But it can also be trained. If you are imaginative in a tactical sense, you can set some sophisticated traps for your opponent.

And with the sophisticated trap, I don’t mean a cheapo that anyone should see in 10 seconds.

The best traps are usually in lines that seem very promising for your opponent.

Maybe it is a forced line that seems to lead to a winning endgame. But in this exact line, you find a very nice resource for yourself that will make the endgame a draw. Your opponent will be attracted to that line because he wants to finish you off.

Ask yourself: what would I like to play as my opponent?

If you can give your opponent the choice of logical moves that do not work, you have a good chance of scoring more points.

With mental stability, a lot of energy, and tactical imagination, you will be able to save many positions on bad days. You will get outplayed or out-prepared, but with these resources, you can score even on such days!

Everyone can win with great preparation and on one’s best days. But only the best also score on bad days. On these days, you can make a difference!

4. Adjust Your Surroundings To Become A GM

You are the average of the five people you spend the most time with.

Jim Rohn

I love this quote from motivational speaker Jim Rohn. It shows the importance of our surroundings. Not only when it comes to performance, but also happiness, wealth, and values.

Spending your time with people that do not share the same ambitions can be tricky. Now I don’t say cut off anybody that is not or does not want to be a Chess Grandmaster.

As a matter of fact, my parents are not very fond of my Chess career and I am still in contact with them.

But I rarely talk about ambitions or goals with them.

Why?

Because they have a safety-first mindset.

They will see all kinds of obstacles and things that can go wrong.

I know they simply want the best for me. But it is not very encouraging to hear 100 things that could go wrong whenever you talk about some ambitious goal.

So think about the people you spend the most time with in your life. Are they really sharing your visions and values? If not, then it is maybe time to change some things up.

Only a tiny percentage of people will stay in your life forever. And that is totally ok.

There is nothing wrong with having a great friendship for years and then splitting up in different directions.

In our hyper-connected world, we have additional possibilities to get the right (or wrong) influences. I include 2 persons I do not even know in my list of the 5 people I spend the most time with.

Through books, videos, and podcasts you can “spend” hundreds of hours with inspirational people without ever meeting them.

Here are some conscious changes I made. I:

- Stopped making fun of Chess as a Sport (and stopped interacting with people that did)

- Analyzed my games with Grandmasters instead of drinking a beer with amateurs

- Interacted with ambitious sportspeople from different sports

- Got a Coach (GM Dorfman) that shared my vision of enter the World Elite

Just try to think about the people you interact with.

Are they bringing you closer or further away from your goals?

It is better to have a few great friendships that give you what you really need, rather than having dozens of friends that drag you down.

Once you start making small adjustments, you will feel huge differences. I promise.

5. Treat Chess As A Sport

Your Chess performance depends on much more than your chess knowledge. The real test is transforming chess knowledge into Chess performance.

While things can look easy if you check games from home with your engine, they are very hard if you sit down at the board and the pressure is on.

So to perform well, one needs to see the whole picture. This whole picture includes:

- Mental abilities (handling stress, recovering after losses, being confident but not over-confident, etc.)

- Physical abilities (sleep, nutrition, sport)

- Chess abilities (preparation, chess knowledge)

I have already written about some of it more specifically in the preparation for tournaments article. Nevertheless, I will shortly give you the benefits of working on each of these points here.

Mental Strength

I had been reluctant to work with a psychologist for a long time. I had a common impression that only psychopaths need to do that. But upon starting in 2015 I felt a huge difference in my life.

Not only my performance in chess got better. I suddenly had a neutral friend to whom I could talk about anything. He gave me already dozens of super valuable tips and insights into how my mind works.

I am still working with the same sports psychologist and the work continues to be valuable. The main aim is to understand me better.

With this understanding, I can take control over the actions on and off the chessboard. Instead of letting emotions control me, which was my default for a long time.

As mentioned earlier, I also use books and podcasts as inspiration and a fountain of knowledge and wisdom. The great thing about working on your mental abilities is that it will benefit you in chess and in your general life.

Without Chess, I would never have taken the step to work on my mind with such effort.

But I am sure I will keep working on my mind even after my Chess career is over.

Physical Abilities

By physical abilities, I simply mean training my body for challenges at tournaments. The Latin phrase

Mens sana in corporse sano

translated as “a healthy mind in a healthy body”, means that mind and body are connected. It is impossible having one part unhealthy and the other at its maximum capacity.

That is why one has to take great care of his body, to achieve high mental performance. The three cornerstones that are most important for my physical readiness are:

- Sleep

- Nutrition

- And Sport

Before my switch, I did not really think about these things. I remember many European- and World Youth Championships where the Swiss team would stay up late, eat fast food, and do little to no sport.

In the most important event of the year, we were jeopardizing our performance with unprofessional behavior.

As you can read in this article, I am now very concerned with my sleep, my nutrition, and the right body activity at tournaments.

I believe that 9 hours of sleep/night plus the right nutrition plus a good amount of physical activity can make the difference when it comes to performing well.

While these things will not improve your chess knowledge, they will help you get your best chess out on day x when it really counts.

And additionally, you will feel and perform better in every other aspect of your life.

Chess Abilities

This is what we all work on most by analyzing openings, studying GM games, or solving puzzles. And it is definitely important to do that work.

But from my experience, there are only small differences when it comes to pure chess abilities at the Top.

What really makes the difference is smart preparation, mental strength, and a body that helps the mind work at 110%.

The stronger you get, the less it will be about improving your chess knowledge, but about transforming your chess knowledge into performance.

That is why you absolutely need to start thinking of the two categories mentioned above if you want to get the GM title.

Summary from IM to GM:

To get from IM to GM, I had to renew my whole approach to chess improvement. No more randomly looking at some games as training. But well thought through training plans that helped me improve.

I needed to make a big step back, to make two ahead. It nearly felt as if I cleaned out most of the things I had learned (in the wrong way) and started from 0. This process can be hard at first, but it worked.

The higher you go up the ladder, the thinner the air will be. And that is why improvement always gets harder.

Winning 100 rating points from 1500-1600 is not comparable to winning the same 100 rating points from 2400-2500. The competition is tough, but with the right approach, one can work through barriers.

What this whole process has shown me is that we are the only ones setting our limits.

It might sound cliché, but I find it is true. Some years ago I would not even think of reaching the Grandmaster title. And now I have rated nearly 100 rating points HIGHER than that perceived limit.

With the right mindset and a long-term approach, I am sure you will also be able to push your limits and reach goals that were beyond your imagination some time ago.

All it takes is dedication, time, hard & smart work, and a bit of luck.

I’m eagerly waiting to hear your success stories.

Sincerely,

Noël